Based in the US, Dr Dhiman Chattopadhyay is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication/Journalism, at the Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania, where he teaches courses in Media Management, Diversity & Media, Strategic Communication, Journalism, and Public Relations. Dhiman, who has a Ph.D. in media and communication from the Bowling Green State University, Ohio, started his career in journalism in the mid-1990s, as a writer for Asian Age in Calcutta. He later went on to work with Deccan Chronicle, The Times of India, India Today, CFO India and Sunday Mid-Day. ‘My research lies at the intersection of journalism, digital media, diversity, and social change. When not teaching or writing op-eds in local media, I enjoy traveling to new countries and sipping my favorite malts,’ he says. Here, he speaks to BooksFirst about his work in journalism, his book Indian Journalism and the Impact of Social Media, the rise of social media and its impact on traditional journalism, and the skills that journalists need in order to thrive in the digital age.

You worked as a journalist for about two decades and were Editor at leading newspapers and magazines in Calcutta, Delhi and Bombay. Please tell us about your early years in journalism? What was it like, being a journalist in Calcutta in the mid-1990s? What was it about your work as a journalist that you enjoyed most, back then?

I had just graduated with a master’s degree in History, when I got an offer to join a new newspaper group called the Asian Age that had recently launched its Calcutta edition (the city was yet to be renamed Kolkata). I still remember that day in 1996 when I walked into the Age’s Prafulla Sarkar Street office – a little nervous but full of eagerness. Today, almost 30 years later, those memories are still fresh in my mind. The friendships I made then, those bonds, are still as strong as ever, even though we live in different parts of the world today. I could probably write a book about those days!

However, when I look back, the thing that really stands out from those days is the camaraderie we had – not just between colleagues within the organization, but across the industry. We were a very young team at AA, with just a few experienced and wiser heads like Tapti Roy and Dibyojyoti Basu leading us. We were inexperienced, but we made up for it with our enthusiasm and willingness to learn, and fight harder to get scoops and exclusives than our more experienced colleagues in other newspapers. And we knew how to enjoy life. We worked hard, and we partied harder. We were not just colleagues – we were friends who watched each other’s backs. We had a young but mature resident editor in Tikli Basu, who scolded, and molded some of the best reporters in the business – Bappa Majumdar, Prithvijit Mitra, Suman Ghosh, and Kinsuk Basu – many of whom went on to become editors. We were dreamers who wanted their journalism to change the world. The revolution may not have happened, but we held on to that spark, and still hold on to the values we learnt back then.

You may have noticed, when referring to journalists in other newspapers, I used the words colleagues and not rivals. I can honestly tell you that I learnt a lot of my craft not just from my AA colleagues, but from my seniors in other organizations – often folks who were fighting with us during the day to get that exclusive story before we could. I still remember calling up the late Sumit Sen (Sumit da, later to become my bureau chief in Times of India, Kolkata) in the Statesman and asking him if I missed any of the beat stories. Without fail, he or his colleagues Anirban da (Anirban Chowdhury), or Anindya Da (late Anindya Sengupta) would read out from their notes what had transpired in a press conference that I had failed to attend, or an important quote that I had missed.

Another thing that I enjoyed was the excitement – the sheer adrenaline rush. It could be that I was doing an investigative story that exposed corruption, or from the thrill of covering an election campaign for Jyoti Basu or a young Mamata Banerjee. But I also remember the tension and apprehension that came from being sent on a 10-hour drive to the middle of nowhere to cover India’s biggest railway accident (near Gaisal in North Bengal, where two trains crashed headlong, killing over 400 people); or the lifetime of memories that came from covering Mother Teresa’s death and funeral – attended by leaders and royalty from across the world. Or, the anticipation when I traveled to England in 1999 to watch a couple of World Cup Cricket games, and wrote about watching Wimbledon live! Like I said, I made friends and memories that will last a lifetime.

Later, when you moved to Delhi and Bombay, did you find the work environment / work culture in those cities significantly different from that of Calcutta? How, and in what ways? In terms of the work culture and working conditions, which city did you enjoy working in most?

I have worked in Kolkata, Mumbai, Ahmedabad, and Delhi; and traveled to Pune almost every year between 2003 and 2014 to teach journalism classes or specific modules. Each of these cities have their own charm. They are different from each other – without being better or worse. Kolkata, I think, was a lot more laid back. Things took their time to happen. People took their time to respond. Well, that part was no different in other parts of India. The bureaucracy always took their time. But life was much more fast-paced in Mumbai and Delhi. I did not work for a newspaper in Delhi. I was a senior editor with Business Today, a part of the India Today group. Naturally, the experience was different. Firstly, I was not out every day, in search of news stories. Second, the way a magazine is run is very different from life in a newspaper. I do not think working conditions were very different, but it was the work culture that was different. Stories took longer to mature, but they were far more thorough than a newspaper piece. To me Delhi’s work culture was always about being perfect and thorough. But it lacked the humane touch, that personal feel of Kolkata.

Mumbai was 24/7. The city truly does not sleep. I have lived in four Indian metros. I have now lived in three different US states. I have traveled and reported from some of the biggest and busiest cities in the world such as Tokyo, London, Singapore, and New York. But nothing beats Mumbai in terms of how alive a city is – whether its 1 p.m. or 1 a.m. When I was working in Mid-Day, my team and I would put the Sunday edition to bed around 12:15 a.m.. I would then pick up my wife Sriya, from her office at Hindustan Times (where she was a senior assistant editor), and drive back to our apartment in Khar. Without fail, the roads would be busy, there would be youngsters coming out of multiplexes or hanging out at a café. People would be coming out or walking into railway stations, and taxis would be ferrying passengers everywhere. This 24/7 culture could be seen at work too. People worked long hours, commuted long distances to work, but seldom shied away from attending a party or having a bit of fun after work. Somehow they managed to extract a 25th hour in their lives. Earlier, when I worked (briefly) with Bombay Times, too, we had so much fun. Work would end at 6 p.m. I would come back home, eat, sleep a bit and then head out to cover a late-night Bollywood event, or a party. Ayaz Memon was our editor then, and he got us to do some great investigative stories. The world of crime, health, education, and civic stories effortlessly shared space with Bollywood glitz, and fashion world glamour back in those days.

Ahmedabad was a surprise. When I moved there in 2004 as Editor of Ahmedabad and Baroda Times of India (the Surat edition launched during my tenure), I was apprehensive. A dry state, and a predominantly vegetarian state! How would a meat eating, scotch drinking Bengali survive here, I wondered. But I not only survived, but those two-and-a-half years in Ahmedabad were so much fun. My colleagues were awesome (I have been lucky enough to say the same thing about my colleagues in all four cities), my team was super cool, and we created all sorts of records during those years. The circulation of all three city editions increased manifold, we held an Ahmedabad Times 10thanniversaryparty in the city – a mega event that had not been organized before, and we broke numerous exciting stories.

It would be hard to pick a favourite but If I had to, it would be Mumbai!

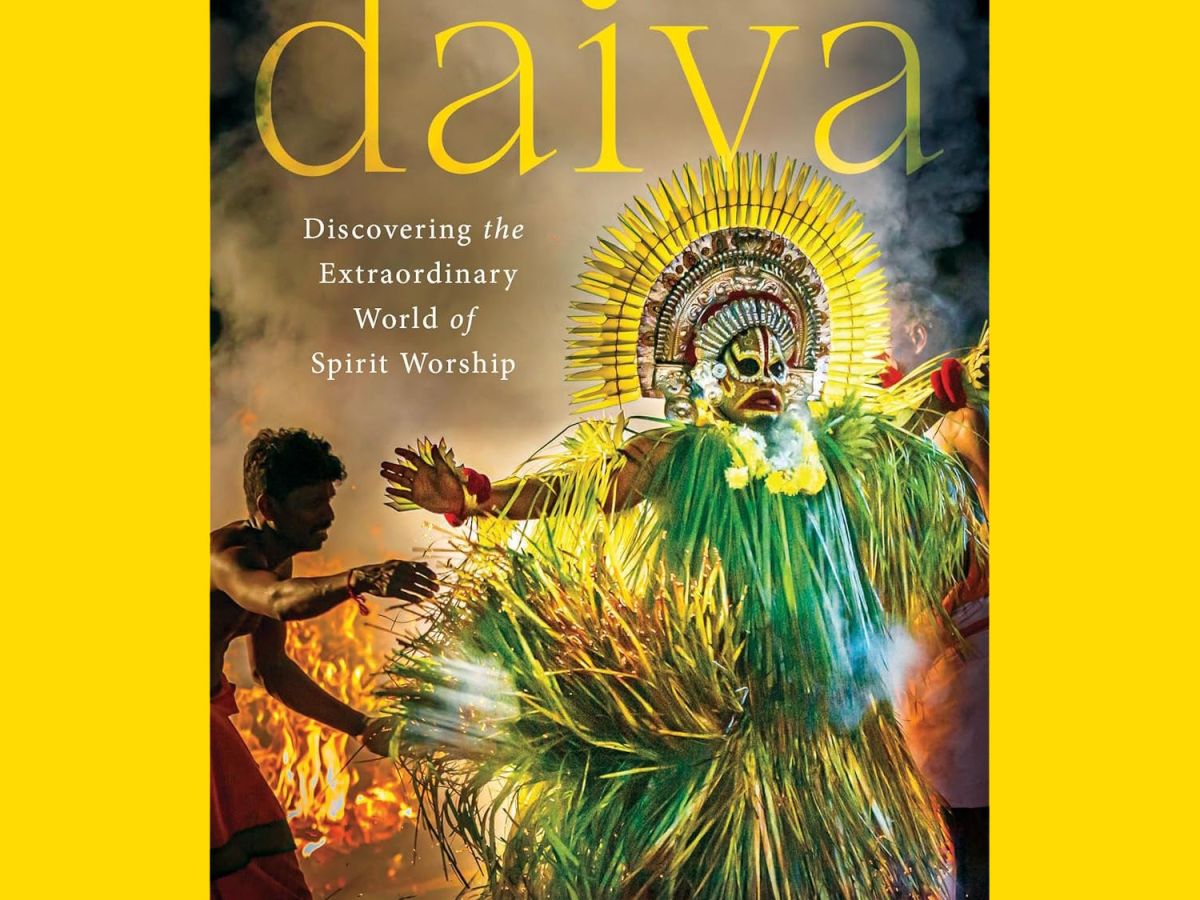

Please tell us about your book, Indian Journalism and the Impact of Social Media. What was it that inspired you to write the book? Any memorable incidents / meetings / conversations that you may have had while researching your book, which you’d like to recount here? Any particularly interesting responses that you may have received for the book, from working journalists, either in India or in the US?

This book is the result of four years of field work in India and of course a lot of writing, mostly done in the US. Don’t think I had any intentions of writing a book when I first started out. The inspiration was a natural one: I had spent close to two decades as a journalist in India, reporting from and editing newspapers, magazines, and websites in four of India’s largest metros. I had seen newsrooms move from handwritten notes, teleprinters, and fax machines, to social media posts, SEO and hashtags. I had witnessed how the world of breaking news has changed. In the 90s, folks would wait eagerly for the evening news or the morning’s paper for fresh news. By the early 2000s that had changed to waiting for the hourly news headlines on TV and the evening newspapers that had scoops the morning paper missed. And by the time I quit the Indian journalism scene in the mid-2010s, audiences were impatiently waiting for a fresh twitter post, or a web update every five to ten minutes to get their fix of breaking news.

Having worked, and led multiple newsrooms through these dramatic and significant changes, I was curious to find out whether my experiences were similar to other journalists across India. More specifically, I wanted to understand how journalists felt about social media’s role as the first source of breaking news, as well as how social media had impacted journalistic work inside India’s newsrooms. Of course, being a solutions-focused journalist all my life, I wanted to know not just what challenges journalists faced, but how they could be addressed.

As I mentioned, this book took over four years to materialize. It involved three separate trips to India, two rounds of surveys of nearly 400 journalists across 15 Indian cities, and in-depth interviews with 25 senior editors and media managers across the country. Needless to say, there were many memorable moments when I met up with my former colleagues – some of them my seniors, or mentors, others my friends, and even folks I had mentored, who had now become editors themselves! For obvious reasons of safety, and other ethical concerns, I could not (and cannot) connect their names to their quotes. In most academic institutions, one must get Institutional Research Board (IRB) clearance before conducting any research involving human subjects, and these rules are rather strict (and rightfully so) when it comes to sticking to the exact methodology we have promised to follow, and carrying out the ethical safeguards laid out in the application document, to a T.

Thanks to the nationwide nature of data collection, I met up with old friends I had not seen in years, folks whom I had known since I was a cub reporter covering education in Bengal. I met with senior colleagues who not only gave me a lot of rich information, but guided me about where to go to find out more. I received tremendous help from folks like Kolkata Press Club president Snehasis Sur, who spread the word about my study and encouraged several journalists to complete the survey. Snehasis da was a star when we were kids, and continues to have a huge influence on today’s young journalists. Others like Sumitra Ray, herself a senior television journalist, helped me connect with editors in television and online media. These people helped me selflessly. I couldn’t offer them much other than a big thank you!

While the book cover does not have words of endorsement from working journalists, I cherish the emails I have from several senior journalists who either took the survey or happily sat for an hour giving me interviews, and then wrote to me to say they were excited that someone was finally doing a scientific, pan-India study of journalism and social media’s impact on newsroom practices.

Did you see journalism in India change and evolve a lot, from the mid-1990s to the mid-2010s? How did the rise of the Internet affect journalists working for print magazines and newspapers? Were they suddenly caught unawares?

This is not a question that has a simple yes or no answer. I wish it had. First, the rise of internet was not all at the same time. Yet, the changes were so rapid and so dramatic that admittedly newsrooms were often caught unawares. Just as we are now struggling to answer how we are going to deal with ChatGPT and other open AI technologies. I remember when the internet was becoming big, we were told in the Times of India that we could use Gmail, apart from the in-house email, because Gmail had so much space that we would not be able to use it up in our lifetimes. We also thought a computer with 1 GB space would be good enough for all our needs. Similarly, when Facebook launched, many folks pooh-poohed it as just another ‘Orkut’ that would be primarily used to catch up with friends, post some images, or go on a blind date. Twitter was going to be that space where we self-promoted our journalistic work! Little did we know that Facebook and Twitter would launch revolutions, fight wars, give us breaking stories and exclusive scoops by the hour – and also flood our lives with misleading information and so-called fake news.

So, yes they have changed our lives and changed journalism forever. To those who denied and sometimes continue to deny or oppose the rise of social and other digital media, my two bits of advice is this: There are things you cannot change, and things you can. Focus on things you can change. You cannot stop the progress of science and technology. What you can do is adapt, as humans have done since times immemorial. Journalists and newsrooms would do wisely to use social media to increase reach, engage directly with audiences, be more transparent about how they get their information and the challenges they face. They should also be more trained and aware of the pitfalls of social media and the information available therein, so that they can both avoid the risk of falling for the trap and sourcing or sharing fake news, and also share their knowledge to help their audiences make better, well-informed choices when consuming any information.

In terms of the quality of content being produced by leading (print) newspapers and magazines today, do you think things have improved in the last 10-15 years, or have quality levels deteriorated?

The very meaning of quality of content has changed in the past three decades. Content is not just what you see in print, watch on TV, or even read on a news website. Content today could mean a TikTok or a YouTube video, an Instagram post, or a Twitter link. These could be from authentic journalists representing a brand, or from journalists gone rogue who are posting whatever they want, instigating people, stoking fear and hatred, and completely disregarding that a thing called ‘facts’ exists – often wearing their biases on their sleeves. Of course content could be from you, me or anyone with access to a computer or an internet connection. And if someone has a huge following on a social media platform, then today they can rival a newspaper or a TV channel for reach and impact. So yes, things have changed – and they have affected journalism.

In many ways, journalism has actually improved. Let me explain. Many journalists today are twice as careful as earlier when they upload a news story on the web. They know that a factual error will be pointed out online or on social media within minutes, and their reputation taken for a ride before they can make a correction. Back in the day, an error would be pointed out in-house – often the next day. In case someone called or wrote a letter to the editor, it was either dumped, or carried in the following day’s (or week’s) paper, with a small rejoinder, or in extreme cases, an apology. Today, we do not have that luxury.

Also, social media had given journalists ready access to political leaders, and celebrities and they can be directly tweeted for a response within minutes. Sometimes, even tagging them in a post can elicit a response. This was just not possible back in the day, when we would have to wait for hours, sometimes days, for an elusive quote.

On the other hand, the quality of online journalism sometimes is appalling. The race to get page views and clickbait etc., has led to misleading and openly untrue headlines. I follow three of India’s leading English newspapers on their app and almost every day without fail there are stories that may suggest that “an Indian legend” has made a “shocking statement” or that a well-known public figure has given an “epic response” to another. But inside – there are no legends, shocks, or epic responses. I understand that news organizations believe they will gain millions of new page views everyday because of these SEO-driven headlines. However, what they may not realize is that over a long term period, such headlines, and such misleading stories lead to an erosion of public trust in media. To worsen matters some of these pieces are a horror from an editor’s perspective – riddled with grammatical errors, and words/phrases that no self-respecting reporter would want their byline associated with.

If you look at the annual trust in media reports that Edelman (or others) publish annually, you will notice that public trust in journalism in India is on a steady decline. While some of this may be due to factors such as increasing political polarization, business control of media, and the pressures on journalists to kowtow to their owners – some of the blame must lie with what is being peddled as “news” in the online space. I must add here that this is NOT a reflection on the hundreds of absolutely amazing journalists doing their jobs against the odds every day – folks who continue to give us great journalism. But the growing number of such misleading pieces, grammatically incorrect copies, and openly biased reportage (often aimed at instigating hate) is a matter of concern.

How was the experience of doing a Ph.D. in media and communication, from Ohio? Did you observe any significant differences in the way journalists and media persons in the US think and work, vis-à-vis their counterparts in India? Also, any major differences in the way journalism is taught there, as compared to degree courses available in India?

My Ph.D. experience was awesome. I know we have had some controversies in India on whether people who are “of a working age,” should be “wasting public funds” in doing PhDs. I was happy to see that in the US – much like one’s gender, sexuality, or social class – there was no bar or stigma attached to being an older adult in graduate school. There were folks in their 40s and 50s attending class and sitting next to folks in their mid or late 20s. We learnt from each other and supported each other. The classes are very intensive, and yet, students have tremendous freedom in what they want to do.

I will not comment on how media persons think in these two nations – simply because I do not have adequate experience of working inside a media house in the US or knowing dozens of journalists personally. So I cannot really compare.

I think at the undergraduate and master’s levels, we are doing a pretty good job in India. I have taught as a guest faculty for many years at Symbiosis International University (at their media and communication master’s program), and the coursework there is both intensive, and inclusive. I have also delivered lectures or conducted workshops at other universities such as Calcutta University’s journalism program, Xavier’s in Orissa, GGSIUP in the National Capital Region and other places. In each case I think they are doing a good job.

However, the manner in which upper level graduate courses and Ph.D. programs are created may be a bit different in the US. For example, in any Ph.D. program here, students need to do a lot of coursework in the first two years. This involves taking around 15 different courses – ranging from classes on research methods (e.g., social scientific, and humanistic), classes that focus on media theories, tools (e.g., statistical tools, interviews, focus groups), or on issues such as intercultural, organizational, or development communication, and their application to our own research. In each class, students would need to author research papers. Again, this taught us not just how to get published, but also the value of detail-oriented work, good research, asking the right questions, and being aware of self-bias. It was only in our third and fourth years that we actually drafted our dissertation (or thesis). This involved making a detailed (in my case almost 100 pages) written and oral presentation before a committee to seek approval to complete the project. Many students either do not pass this proposal defense, or take multiple attempts to pass. So, yes, it is fun but a lot of work.

In terms of video content, what is your take on the phenomenon of traditional media houses having been put on the back foot by individual content creators who have become superstar ‘brands’ unto themselves and have millions of followers? In so many cases, why are traditional media houses – with trained journalists and significant resources at their disposal – unable to take on individual content producers, who are able to do much more with much less?

In one sense I think it is a good thing that we have what is often labeled the “democratization of news.” Traditional media houses are increasingly being monopolized by big businesses where media is often seen by the owners as a propaganda weapon. Journalists are feeling the heat. One way to fight back against big media is to support smaller groups or even individuals trying to present unbiased, fact-checked information to audiences. And if the world has moved to consuming information on their phones, and via 60 second reels – then there is no harm in using the same platforms to present news. After all good journalism must reach audiences where THEY are, and not just be present in a space because journalists are comfortable there.

Having said this, I will repeat what I said earlier – that no technology is one-way traffic. Much like atomic energy can be used for good or evil, social media too can be misused. And there are enough folks who are doing that. Sadly, many of them also have huge fan followings.

Media houses must do two things on an urgent basis. First, invest in training ALL their staff in basic video production, including editing and uploading for multiple platforms. And second, stop using the online space as simply a clickbait tool. Yes, there are dedicated online teams in most media houses, but they are mainly content editors and uploaders. When you are on the spot – you need to be able to shoot a video, edit it on your phone or gadget, add voiceover and send it for your team to quickly put it out there without wasting time. If only a select few have this skill within a newsroom, then independent citizen journalists will continue to outsmart them. We need citizen journalism – make no mistake. But there are no checks on what such “journalists” put out. Traditional media houses need to be able to counter that with speed and skill.

What is it that you find most remarkable about digital storytelling? Would you like to name the three most important elements about journalism / storytelling in the digital age that make it markedly different from the pre-Internet era?

There are several questions here. Let me try and answer each of them briefly. As far as digital storytelling is concerned, the biggest takeaway for me is that is allows a journalist to use text, audio, and video all at once to tell a story online. A digital story can have 300 words of text, but it can also have an embedded video, an audio component (such as excerpts from an interview), several still images, and multiple hyperlinks guiding audiences to other related stories, images, videos, or audio clips. Well-crafted digital stories can hook audiences for a long time.

I think what makes journalism today markedly different from the pre-internet era, is the ability of different apps, social media, and other web-based platforms to break news almost as it happens, and the resultant public expectation that journalists and newsrooms will also keep them informed every few minutes and 24/7.

The availability of latest information on a 24/7 basis on websites of traditional media organizations as well as on their official social media handles, has increased the reach and scope of news beyond what we could imagine in the lats 1990s or even early 2000s. Today, if there is a shooting in New York, then audiences in Mumbai learn about it as quickly as audiences in New York do! When publishing a story on the web, journalists know that their work is instantly available to audiences all over the world. Connected to this, another big change is the journalists today can and must report any breaking or developing story immediately. They cannot take six hours to wrote it for publication in next morning’s newspaper. The third big change is that digital storytelling has brought journalists and their closer than ever before.

I must add an important caveat here. When we are speaking of digital audiences and digital storytelling, we are primarily thinking of the elite in India – those with access to internet, smart phones, and other gadgets. Even though internet is now available far more widely in India than 10 years ago, the digital story audience is primarily the urban, educated, middle class. Millions more may have access to internet but may not consume news on TikTok, Twitter, or on web-based news apps. So, side by side with digital storytelling, more traditional formats must continue to flourish.

Do journalists today need a completely different set of skills, as compared to what was needed 20 years ago? Do you think most older journalists have adapted well to the current scenario, or do they need extensive re-training in order to stay relevant?

At one level, journalists obviously need to recalibrate and learn new skills to adapt to this changing world. With every passing year, more and more Indians will get connected to the internet and consume news via social media and other web based apps. What skills would journalists need? They might include learning how to write for a digital audience where even headlines need to be more SEO-focused. If a story’s headline, shoulder, and the first paragraph (perhaps even the photo captions and info box sub-heads) do not include words and phrases that audiences are likely to include when they search for that specific news or topic – then a wonderfully researched story may fall flat and not even be noticed by intended audiences. Hence, learning to use keywords, understanding how the concept of SEO works, is vital for all journalists and not just online teams and copy editors.

Similarly, journalists should try and learn new tools such as how to use platforms such as TikTok or even Instagram more effectively. For example, a You Tube video can run for 15 minutes. But folks on Tik Tok will not watch anything that is over two or three minutes in length. If journalists are to grab the attention of those in the 16-24 age group, then stories must be posted on Instagram, Tik Tok, and even Snapchat (as of 2023. No one knows what 2024 may bring) and formatted to suit those platforms. It makes zero sense to post stories on Facebook if you want to grab the attention of younger audiences. In he US for example, Facebook is used primarily to target the “parent” audience, whereas Instagram, Tik Tok, and Snapchat are the platforms to go to if information is aimed at high schoolers and university students. Those who resist technological changes will fall behind because none of us can stop such large scale change from happening.

On the other hand, some skills are golden and must be learnt by the new school of journalists trained in social media skills, but forever in a hurry to post breaking news first, before anyone else. They must re-learn skills (or traits) such as source verification, cross-checking facts, getting both sides of the story, and other ethical issues. For example, is it ok to simply pick up someone’s tweet and use it as part of your story – without checking the context of the quote, or asking if the person was ok with being quoted? Would you not need to ask a person’s permission before interviewing them?

What are you currently reading? What kind of books do you enjoy reading? Any favourite genre? Favourite authors? Any favourite Indian authors?

Apart from academic books, I am currently reading a book by Isabel Wilkerson, called Caste: The Origins of our Discontents. And no, this book is not on the Indian caste system. Instead, the Pulitzer prize-winning author argues how the history of United States is a history of a hidden caste system, and “a rigid hierarchy of human rankings.”

Normally, I have enough serious business going on in life. So when I relax, I either read crime fiction or graphic novels – sometimes even comics! We own the entire collection of Sherlock Holmes stories, as well as all Agatha Christie novels that feature Poirot or Miss Marple. I can re-read them multiple times. They never get old. I also love reading ‘comics’ such as Calvin & Hobbes, Dilbert, and some of the old Bengali classic comics such as Hada Bhoda and Nonte Phonte. Perhaps not quite what you expect from a university professor, but I’ve never been one to conform to stereotypes.

Among Indian authors, I love reading the works of several Bengali authors. Again, these are folks who made us laugh – Shibram Chakrabarty, Narayan Gangopadhyay, and of course Satyajit Ray who wrote hundreds of stories and novels for the young and old alike.

adventure advertising Apple astrology audiobooks Banaras best-of lists Bombay book marketing business Calcutta cheap reads cityscapes corporate culture crime design fiction food Hinduism hippies history India Japan journalism journalists libraries literary agents memoirs memories money Mumbai music my life with books Persian photojournalism publishers publishing religion science-fiction self-help technology travel trends Varanasi wishlists