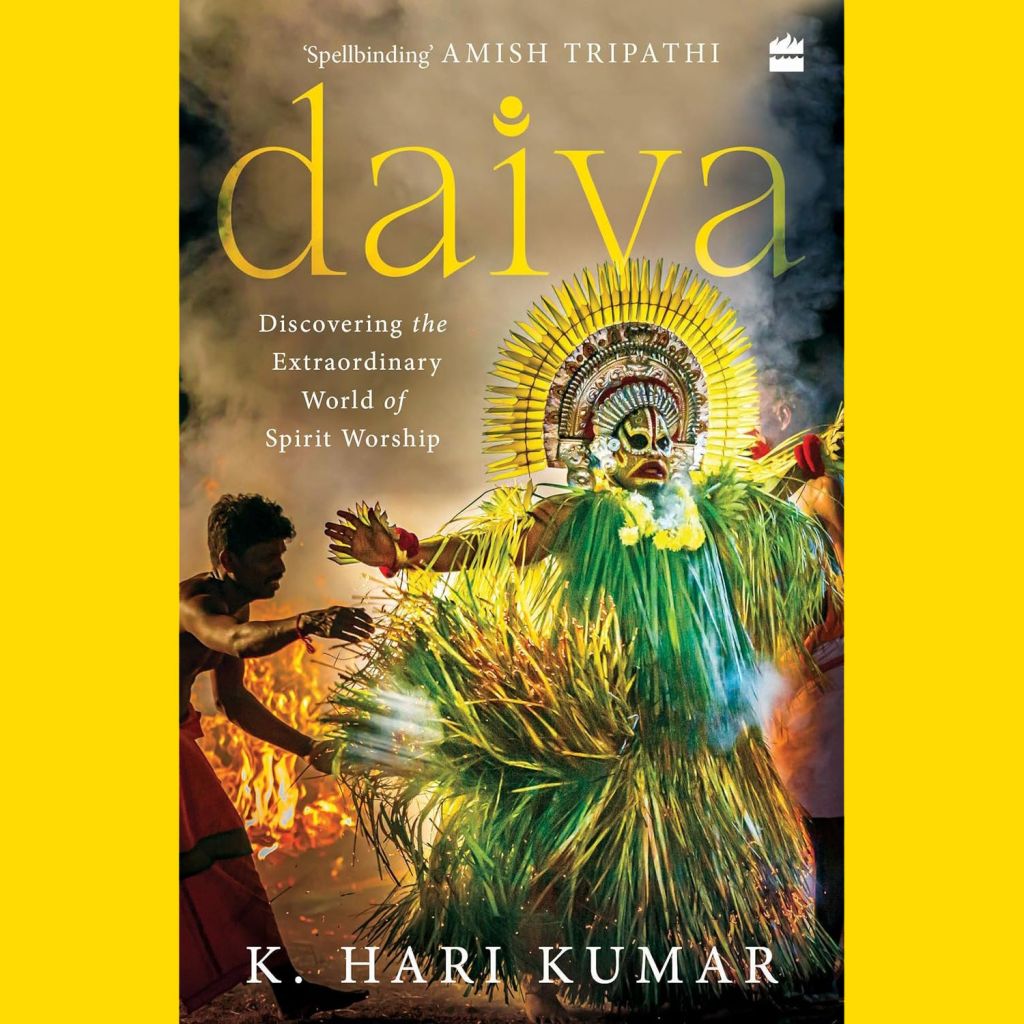

‘The famous Kola performances of Tulu Nadu involve dancers who invite powerful, sacred spirits to possess them. Through the performers, and surrounded by vibrant colours and striking visuals, these spirits – known as daiva – may settle disputes, provide guidance, grant blessings and pass judgement. However, there is so much more to it than art and devotion. From Panjurli, the benevolent boar spirit to Bobbarya, guardian of the sea, this book explores it all: the kinds of daiva, their stories, their individual natures and the ways in which they come to inhabit the devout. In Daiva: Discovering the Extraordinary World of Spirit Worship, author K Hari Kumar, brings you stories of powerful immortals along with details of their worship through mystifying rituals – all of which are known to leave onlookers awe-struck,’ says the publisher’s note.

‘As I delved deeper into the traditions of Tulu Nadu, I became increasingly fascinated by the worship of daivas. The very mention of a daiva would send goosebumps to those who believe in the spirit deities. Such is the power of devotion. Daiva aaradhane or the worship of spirit deities is integral to Tulu culture. My quest to find out about my roots drove me, and ultimately inspired me to pen this book, a tribute to the rich cultural heritage of Tulu Nadu,’ says Hari Kumar. ‘My purpose in writing this book is not to present an academic treatise on daiva aaradhane, nor is it a critical analysis of the subject or a commentary on the present-day politics surrounding it. I am neither a practicing expert nor a scholarly erudite to impart such knowledge to you. Instead, I seek to embark on a personal journey, as a migrant Tuluva, a writer of genre inspired from folklore, to unravel the mysteries of the spirit world and trace my roots in the land of the naagas and daivas,’ he adds.

With the publisher’s permission, here is an excerpt from Daiva: Discovering the Extraordinary World of Spirit Worship

A few years back, I was invited to join a panel at a prestigious literature festival, and let me tell you, a horror panel getting a spot in a big literature festival felt like winning the lottery—or at least, like finding a ghost under your bed. Jokes apart, there I was, on the stage, watching my co-panelist eloquently speak about the usual Western supernatural creatures—blood-sucking vampires, broom-riding witches, and night-howling werewolves. I couldn’t help but notice that when he began to delve into Indian entities, he was equating them with their Western counterparts.

Similarly, on a podcast, I chanced upon another prominent author expounding upon prethas and bhutas. But once again, I couldn’t shake the feeling that this too was being articulated from a Western perspective. While certain concepts overlap in spirit and ancestor worship, it became clear to me, after interviewing experts for my book, that there is no consensus when it comes to certain terminologies. In fact, the concepts change from family to family, village to village, district to district and state to state, across the country. There is a different view of the local scholars which may contradict with those who are practicing the rituals. As seeker of all things existential and beyond, I think it is my duty to explore the true nature of these ethereal elements from an objective point of view, and not be swayed by bias, but it remains essential to classify spirits subjectively, at least for the span of this book.

Where do spirits come from? Do they live in our world? Do they live in another realm? Is this spirit realm coexisting in ours or on another dimension? To understand the concept of the spirit realm, we must probe deeper into the intricate world of Indian lore and spirituality. As I do so, my mind is consumed by contemplation of the definition and etymology of the diverse terminologies that encompass the realm of spirits and deities. Each word bears a wealth of significance, steeped in a unique history in different regions of our country that intricately interweaves with the rich fabric of the broader ‘Indian culture’ that is perceived by the outside world. And yet, as I ponder over their profound implications, I am humbled by the realization that my understanding remains a work in progress, constantly evolving as I unravel new layers of complexity, results of which you will find in my future works in this genre.

In the Hindu scheme of things, the concept of death, referred to as dehanta, is rooted in the amalgamation of two terms, ‘deha’ and ‘anta,’ which literally translates to ‘the end of the body’. At the moment of death, something departs the deha, signifying the soul or spirit, comprising only vayu (air) and aakasha (ether). Whether this soul encapsulates consciousness or if it’s the other way around is another debate. After this, the performance of proper funeral rites become imperative to facilitate the ascent of the departed soul to pitr-loka. In the Garuda Purana, it is mentioned that the one who doesn’t obtain antyeshti is condemned to wander eternally as a ‘preta’ (pretha if you are from the south). Antyeshti is composed of the words antya and ishti, which respectively mean ‘last’ and ‘sacrifice’. Together, the word means the ‘last sacrifice’. It is also commonly referred to as antima sanskaara, kriya karm, etc. As the traditional religions of India are based on the belief in rebirth, pretas, therefore, are destined to suffer as incorporeal spirits in the afterlife because of their insatiable hunger and thirst.

Sometimes they cause harm to humans.

The concept of pretas and their potential to cause harm to humans shares similarities with the widespread global belief in ghosts. In various cultures worldwide, there is a shared understanding of incorporeal spirits that may haunt people or places after death. Many a times, preta and bhuta are used interchangeably. Let us now turn our attention to bhuta, a term that refers to the ‘past’ or ‘something that existed in the past’. In our popular culture and literature, the bhuta is a supernatural entity, often described as the ghost of a deceased person. The nuances of how bhutas come into existence vary depending on the region and community, but what is common among them all is that these spirits are often perturbed and restless, unable to move on to their next life. This inability to move on may be due to a violent death, unresolved issues in their past lives, or even improper funeral rites performed by their survivors.

It is interesting to note that bhuta has different connotations in various texts. For instance, in the Shivapurana, bhuta refers to the five ‘elements’, while in the Natyashastra, they are assigned as protectors of the natyamandapa or the stage where dance is to take place. In Jain scriptures, bhutas belong to the vyantara class of gods (devas), comprising eight groups of deities that roam the three worlds. The bhutas may also refer to Shiva’s attendants in Kailasa that are part of the bhutaganas. It is worth noting that in the world of Tuluvas, bhutas are not always malevolent spirits, but rather protective spirits and deities. In Tulu Nadu, all communities place great faith in bhutas. When any calamity or misfortune befalls a family, propitiating the bhutas is considered essential. The worship of bhutas has evolved over time, blending elements of both primitive and puranic propitiation.

The word daiva in Sanskrit means relating to gods, caused by or coming from gods, divine, or celestial. According to some scholars and experts, daivas are those spirits which have originated from a divine source or from prakriti (primordial creative force). There is a rigid hierarchy within the pool of daivas as well. The term daiva or daivangalu is usually applied to those (spirit deities) of higher order that do not partake in animal food. This distinction may have originated from the influence of Brahminism and Jainism, both of which advocate vegetarianism. In contrast, some bhutas may accept non-vegetarian and liquor offerings.

Daiva: Discovering the Extraordinary World of Spirit Worship

Author: K Hari Kumar

Publisher: HarperCollins India

Format: Paperback / Kindle

Number of pages: 272 / 319

Price: Rs 327 / Rs 310

Available on Amazon