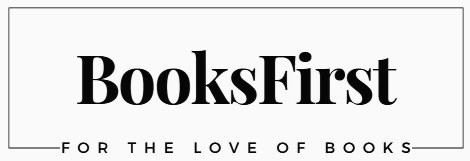

Delhi-based Dr Jindal is a senior primary health care physician, with close to four decades of work experience. She is also the author of The Reluctant Doctor: Stilettos to Stethoscope, a memoir of her four decades of medical practice in rural India. The book is about ‘stories of learning, growing, trying to make a difference, making mistakes, searching thousands of faces for disease and watching a population destroying themselves as liberalisation hit India in 1991,’ she says. We talk to Dr Jindal about her work and her book, and also present an excerpt from The Reluctant Doctor.

From being a doctor and working in medicine, to writing books – please tell us more about the journey. What is it that inspires you to write?

I have been writing poetry and short stories from a very young age. These were published in various magazines and journals even when I was in school. This passion was relegated to the background for many years as I grappled with setting up my rural practice, which was challenging enough.

As thousands of patients walked into my clinic, I observed them intensely and found myself wondering about their lives, relationships, their sadness and joys. I stored all their stories in my mind hoping to retrieve them later. I was lucky that I didn’t need to look for my muse and inspiration. I have spent years searching and probing them and trying to decipher their emotions. Faces fascinate me, pique me and make me wonder at the number of masks we all carry within us. It is this passion to study faces and unravel their thoughts that intrigues me as a writer and an artist.

I saw my colleagues climbing up the professional ladder in big hospitals in India and abroad and my small, rural clinic was humiliating and embarrassing. When there is dissatisfaction, dissent and discontent, the desire to explore new avenues becomes very strong and one starts to trod on untrodden paths, and I found solace in art and writing.

Tell us more about your new book, The Reluctant Doctor. How did you background in medicine help you in the writing the book?

The Reluctant Doctor is a poignant tale of a reluctant, young doctor who found herself hurled from an urban lifestyle to managing a rural clinic and it is an honest account of how the rural patients and their stories became a sustaining force for her over the decades. I was uprooted from an affluent lifestyleto give up my dreams of specialising in pediatrics and wearing sharp pencil skirts to work in England. Shattered dreams, a lost lifestyle and belittlement by colleagues, I managed to find my calling in the remote village. A doting father’s vision of setting up a charitable clinic in a small village saw me treating hordes of patients from hamlets far and near.

As thousands of patients streamed in the small clinic, my priorities changed and soon my privileged life seemed frivolous. Treating the fifth generation of the families that adopted me as their ‘family doctor’ thirty-eight years ago, gives me a linear insight into family dynamics. Being a first-hand observer of this tectonic shift in family and societal values, I recount these tales in a simple relatable voice.

The book has received good reviews from readers, critics and medical colleagues. Some of my colleagues were in awe of the silent journey I undertook forty years ago, resisting the temptation of greener pastures abroad.

Please tell us more about your 40-year journey as a doctor? Since the time you started, in the 1980s, how has the medical profession itself evolved in India?

This is a vast question and probably needs another book. Over forty years of practice, I witnessed the changes in lifestyle and the insidious scourge that fast foods and western luxuries brought to our idyllic villages. Globalisation, laced with the land boom of the 2000s, brought with it sacks full of money that the farmers had no use for. It brought with it an euphoric entitlement by idle village lads, leading to rapes, marital abuse, murders, bride burning, female foeticide and suicides.

The world of medicine has changed a lot in the last four decades. New technology, faster diagnosis, latest machines, robotic surgery, multimedia teaching and better medicines have all made lives better in the urban settings. Rural and affordable medical care is still in the nascent stage and may stay that way if doctors are not offered incentives to practice in rural areas. Young doctors are making a beeline for better prospects abroad. No one is interested in a simple GP practice. Super specialty hospitals beckon all.

What kind of books do you enjoy reading?

I love the printed word so much that I would even read the newspaper wrapping that fruits and vegetables sometime come in. I love to read autobiographies and books about real people. I love short stories too. Dubliners by James Joyce is my all-time favorite. Socrates Express is another favorite that I can read and reread any time. At present, I am reading Girl in White Cotton by Avni Doshi.

An excerpt from The Reluctant Doctor:

The men operated the tractors, cut the sheaves of the grain and put them in the threshers to be thrashed into pearls of golden wheat separating them from the chaff. The sheaves had to be put right inside the machines with the whole arm. Obviously, the ruthless blade did not distinguish between human and botanical matter, so many patients visited me with sliced fingers, chopped hands and a few times, a few young men had their arms hacked off by the machine. In fact, every village had a sizable number of men with just one arm, but they carried their remaining arm with pride, as a soldier would. There was no shame as this was considered an accident of valor.

There was this young guy who refused to go to the hospital. In those days, people feared hospitals because they were strange and unknown places. Anyway, this lad of twenty-something had cut his index finger in the hay machine. As he unwrapped the blood-soaked cloth from his hand, thin tissue kept his finger attached as it hung and dangled all over the place. I knew nothing about hand surgery, and this was a lacerated wound with uneven skin tags ready to fall off.

“I’m sorry, but you must go to the hospital, I can’t do this,” I said resolutely. “I am not going to any hospital,” he argued. “I will just go home and let it heal.”

He got up to leave, but before he exited the room, he turned back to me.

“Either you do whatever you can do, or God will help me.” I looked at his mother, who nodded in agreement with her son, of course. She had an unwavering faith in my skills. So the family and my staff all agreed that I was the best person to undertake this task. Convinced by their conviction, I got the tray, suture material, curved needle, and swabs.

I admit that I lacked the posh machinery they had in hospitals, but I was proud of my stitching set and the best suture material available in the country, thanks to ‘new husband’. He made sure I had the best self-dissolving catgut, top-class curved needles, the sharpest forceps and stacks of sterile gauze. Sterile gauze and Sofra Tulle were a real luxury in that era because no one had seen or heard of them, and they were costly. Yet, I had an ample supply of these. When the tools are right, the job at hand gives immense joy. So was the case with stitching procedures that I undertook in my clinic.

The cost of the materials I used far exceeded the payment I received for my service. Yet it never bothered me as I was immensely proud of my artful procedures. Even the tape I used was different from the tape other doctors were using those days. It was a high-end tape that did not hurt the patients when I pulled it off the next day.

I washed the wound thoroughly with saline, but the more I looked at the hopeless digit, the more I knew the grave mistake I could be making. I carefully aligned the finger and slowly worked my way around, stitching it neatly, tag by tag until all the skin tags were joined together. Patience was the key. I had that in plenty.

After my artistic stitching, the finger looked fine from outside, but the blood vessels and nerves that may have got injured had to be overlooked. After I stitched his finger, I prayed for his recovery, and looked at the boy’s face. He looked good to go with a victorious look that said, look, I told you, I knew you could do it!

I could have gloated, but the fear of the boy developing gangrene haunted me for a week. I warned his family that he had to visit me daily for a new dressing or I would have to send him to the hospital if the digit changed color. I continued to worry that his finger would turn black, which was a precursor to gangrene. Gangrene was the biggest fear of all doctors.

My confidence increased with stitching wounds of all sizes and different types of cuts. I knew that if I refused to stitch up a patient, they would just go home and wait for it to heal on its own. No one would ever go to Safdarjung. As a result, I stitched many wounds, and I was soon adept at most wounds. I prided myself that not one injury, ever, got infected. Sterilization, proper washing, judicious wound care and daily dressing with the correct dosage of antibiotics and a daily dose of my morale-boosting advice ensured perfect results. However, I had not yet ventured into detached body parts. There were lacerated wounds, infected ones, wounds that had no shape, and wounds that wouldn’t stop bleeding. How could anyone stitch them? They had no edges. I saw them all with certain confidence laced with nervousness. Whatever I did, my hand was always steady, thanks to the training I had had from Lady Hardinge Hospital.

It was just another day at the clinic when one of these ill-starred guys came to visit me in my clinic. He walked in with another young male, both of whom strode with stoic confidence to ward off the pain. I never got used to seeing a man carrying his detached limb in a dirty towel. Here was this young man carrying the whole limb in a towel with not a wince or whimper.

“Please manage this,” his aide commanded, looking at me without an ounce of doubt. “What?” I recoiled at the sight of the freshly chopped limb. It was still oozing blood. “You did my brother’s finger,” the aide said without much ado. “That’s why I came to you.” I did not want this kind of exaltation. My mind did all the cartwheels that it could, to get out of the situation. “No, no, take him to the hospital,” I said looking at no one in particular. “I can do the first aid to stop the bleeding. Take him to Safdarjung. They will do a good job.” I knew I was not equipped for attaching chopped limbs.

Luckily, there were no arguments, and they agreed to go to Safdarjung.

The armless man sat stoically while I administered first aid to him and gave him an injection for pain, and soon enough, I saw him off to Safdarjung Hospital, which was about 20 km away.

The Reluctant Doctor: Stilettos to Stethoscope is available on Amazon

adventure advertising Allahabad Apple astrology audiobooks Banaras best-of lists Bombay book marketing business Calcutta cheap reads cityscapes corporate culture design fiction food Hinduism hippies history India Japan journalism journalists libraries literary agents memoirs memories money Mumbai music my life with books Persian photojournalism publishers publishing religion science-fiction self-help technology travel trends Varanasi wishlists

More Stories:

adventure advertising Allahabad Apple astrology audiobooks Banaras best-of lists Bombay book marketing business Calcutta cheap reads cityscapes corporate culture design fiction food Hinduism hippies history India Japan journalism journalists libraries literary agents memoirs memories money Mumbai music my life with books Persian photojournalism publishers publishing religion science-fiction self-help technology travel trends Varanasi wishlists

One response to “Balesh Jindal: The Reluctant Doctor”

The reluctant Doctor sounds interesting. Will surely try.

LikeLike