Goa. For a lot of people, it’s their idea of paradise. White beaches. Blue water. Cocktails and a balmy sea breeze. Snoozy, lazy days. Parties in the night. A relaxed, chilled-out Goan lifestyle that’s a world away from the helter-skelter of a Delhi or a Mumbai. That’s the dream, right? Sure, and for a lucky few, that’s exactly how things might work out. For many others though, the reality of Goa might be a bit different. If you’ve always thought about what it takes to truly become Goan, Michelle Mendonça Bambawale’s book, Becoming Goan, gives you the lowdown on what it’s like. ‘In June 2020, Michelle found herself moving to the 160-year-old house she had inherited in Siolim, a village in North Goa, with her human and canine family. Having never lived in Goa before, she couldn’t help but wonder if her Goan ancestry made her an insider or if she would forever remain an outsider. In this memoir, she confronts her complex relationship with her Goan Catholic heritage and explores themes of identity, culture, migration, stereotypes and labels,’ says the publisher’s note. ‘She also takes us back to Siolim and Goa of the 1970s and 1980s, where she spent her summer vacations, without paved roads or electricity, pulling water from a well. Today, she dodges reeking septic tankers, earth movers and piling plastic garbage while walking her Labrador, Haruki. Becoming Goan is a heartfelt and charming story of Michelle’s love for this land that her grandparents left her,’ it adds.

Born in Pune in 1966, Michelle moved to Bombay in the mid-1980s to study and went on to work in advertising, with Ogilvy. She got married in 1989 and later moved to Dubai with her husband, where she spent a good ten years, after which they also spent a few years in Thailand and in the UK. They came back to India in 2011 and the plan was to continue working in Delhi/Mumbai for a few years before finally retiring and moving to Goa. However, the Covid-19 pandemic happened and the family relocated to Goa in 2020. ‘I was looking to find safety in a place my grandparents had left. Over the years, coming to this house has given me a sense of belonging. I feel a connection to a culture that was familiar, yet alien,’ she says, adding that she’s always had a complicated relationship with her Goan lineage as she’d never lived in Goa full-time and neither did she speak Konkani. The latter, she says, is ‘tragic, as language is the key to a culture. In any case, they moved to the house her grandfather built in Siolim back in 1859, which Michelle and her husband had extended and modified (in order to add contemporary creature comforts, while keeping intact the basic structure of the old house) in 2009. Christened ‘Casa Mendonca,’ this would now be the family’s permanent home in Goa.

Michelle writes about having to search for her true identity once she’s in Goa. She struggles with finding answers to questions about whether she really belongs there and if she’s a ‘real’ Goan, or an outsider who has returned to her ‘native place’ after spending years in various cities around the world. She also feels some pressure of getting her memoir – her Goa story – just right, since it would entail the responsibility of documenting the current state of Siolim, and Goa, itself. But she seems to relish the challenge and wades in with gusto. There are some hard questions that must be answered. For example, will the Goan identity survive in contemporary Goa? What is unique – and special – about Goa and about Goans themselves? And then there is the village of Siolim itself, with all its stories and legends, the way things used to be in the Goa of the 1970s-80s and how things have changed and evolved (and brought chaos to Goa in the process), Portuguese property laws, how these are still in effect in Goa and how they make things complex for those who are either inheriting property there, or wish to buy a house in Goa, the challenges of managing a house in Goa (which includes dealing with assorted wild animals and creepy-crawlies), understanding Goan celebrations and local traditions, and more.

Michelle’s memoir is quite the eye-opener and makes it clear that romantic notions associated with living in ‘an old Portuguese house in Goa’ aside, the Goan dream might not be for everyone in the actual, real world. Some of that is, of course, due to overcrowding and the fact that the place seems to have been run over by hordes of uncaring tourists. ‘The current amalgamation of cultures is moving from Goan and Portuguese to Bollywood on one hand and globalized capitalism on the other. You can hear loud bhangra beats in shacks, dished up with generous helpings of chicken tikka, served with a side of mutter-paneer,’ says Michelle. Older Goans complain about unpredictable and frequent power outages, exorbitant prices, rampant corruption, dirty and overcrowded streets, and even hordes of rampaging monkeys who destroy roof tiles and damage trees and other plants. Those Goans whose parents or grandparents were born in Goa before 1961 are eligible for Portuguese citizenship; some of them have a Portuguese passport and want to sell their ancestral land/home, and relocate. It’s a state of social and cultural influx – the locals want to move out, while swathes of ‘outsiders’ want to buy property in Goa and move in. Michelle says it’s hard for her to identify with one or the other of these two and that she doesn’t know whom to identify with. ‘I was caught in the middle, defending Goans to everyone else and defending outsiders to Goans,’ she says.

Goa is certainly India’s favourite party town and that party, says Michelle, started in the early-1950s when the first starred hotel in Goa opened up. In the 1960s, Goa attracted hippies from across the world, complete with their psychedelic clothing, music, drugs and liberal attitudes towards sex. And indeed, Goa back then – with its serene, secluded beaches, quiet villages and the simple life – really must have been the closest one could get to paradise while still being alive. Things started changing in the mid-1970s and early-1980s, when big-name hotel chains set up shop in Goa, ultimately paving the way for mass tourism and completely changing its earlier European/Portuguese vibe to one that more closely matches that of the rest of India. The answer to whether that’s unfortunate or an inevitable part of ‘progress’ depends on whom you ask. And while we’re trying to figure out that, the Israelis and the Russians have muscled their way in and have ‘colonized’ parts of North Goa – things have gotten to the point where some restaurants now don’t even allow Indians to enter their premises – only Russians are allowed entry. If that weren’t enough already, word on the street is that the Sudanese and the Nigerians are beginning to get in on the act and are now dabbling in drugs and weapons right alongside the Russians. More? There’s illegal sand mining, gambling, floating casinos… you get the drift.

All is not gloom and doom, though. Michelle, in her eloquent manner, writes about Goans’ love for their land even if they have to migrate to other places for higher studies and/or to find jobs. And of the laidback, Goan way of doing things (‘why do today what you can do tomorrow?!’), their relaxed attitudes towards mundane things like punctuality, their suspicion of every car that does not bear a Goa numberplate, their need to eat fish at least five (if not seven) days a week and their distrust of all outsiders. One of the best parts of the book is where she describes her holidays in Goa in the 1970s-80s, which makes you wish Goa had remained the way it was. ‘In the 1970s, Siolim was truly pastoral – coconut trees and fields, a few grand old houses, hills to climb and backwaters to explore. Over the last fifty-seven years of my life, other than the church and the Chapora river, everything else has changed,’ says Michelle. She writes of her memories of Mapusa market, which she used to visit for Goan sausages, cashew nuts, puffs and doce, falooda and assorted trinkets. ‘We often ventured out and took buses everywhere. Taxis were very few and unaffordable, and the travel took half the day, but we didn’t care – it was an expedition and we had plenty of time,’ says Michelle and notes that then, as now, these buses run totally packed and smell of ‘stale sweat, fresh fish, dried chillies and other special Goan aromas.’

Over 275-odd pages, Michelle paints an exquisite picture of Goa – her Goa, your Goa, the Goa of tourists’ dreams, the Goa of its long-term inhabitants and many others. In this, she is able to give you a clear idea of what it was like to live in Goa 50 years ago, how things have changed, and what’s good, bad and ugly – take it or leave it. She writes wistfully about the wide open spaces, the fields and the fruit trees that were once everywhere and which are now much harder to find. And she wonders if Goa’s beaches and its unique flora and fauna will survive and whether it’ll all still be around for her children and their children to enjoy. In the future, will Goa be all about gentrified gated communities, luxury villas and golf courses, she wonders. However, she ends the book on a hopeful note, underlining the fact that this is a land worth fighting for and that we must strive to preserve Goa’s environment and ecology while enjoying its undeniable charms. Her stories are wonderful and are told with the elan of a talented writer. For anyone who’s in love with Goa and who’s ever thought of moving to this magical place, you certainly won’t regret getting a copy of this book.

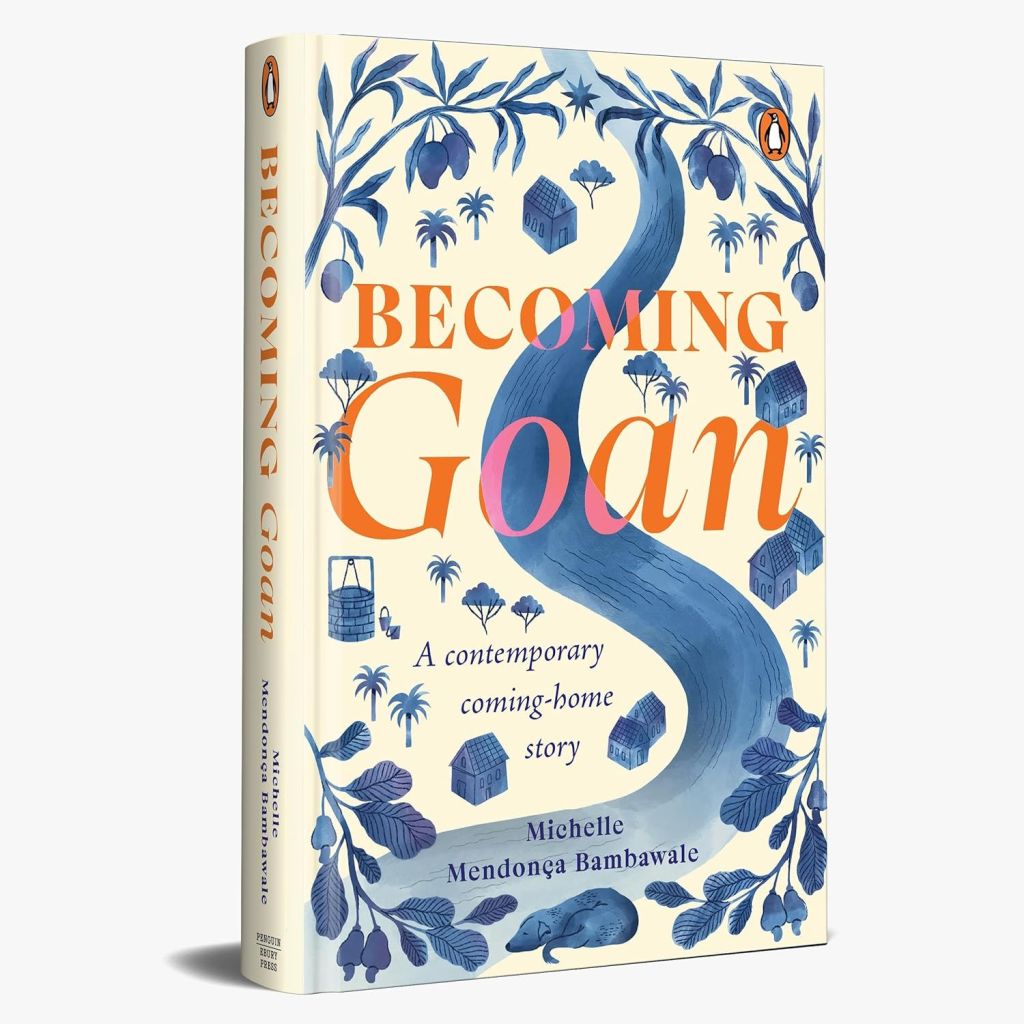

Becoming Goan: A Contemporary Coming-Home Story

Author: Michelle Mendonca Bambawale

Publisher: Penguin India

Format: Paperback / Kindle

Number of pages: 288 / 278

Price: Rs 299 / Rs 288

Available on Amazon

Book Review: Becoming Goan – A Contemporary Coming-Home Story