Think about this for a second. There are currently more than a billion websites in the world, about 200 million of which are active. Two hundred million active websites. And here you are, on BooksFirst, reading about Fluke. In the larger scheme of things, how random is that? What might have been the probability of you ever visiting this website and spending 2-3 minutes of your life reading this particular article? Infinitesimal, perhaps. And yet, here we are. Pure chance? Think about the biggest movie stars, the richest businessmen, and the most successful people in the world, regardless of what their profession might be. How did they get there? Are they necessarily the smartest, brightest, most talented, most knowledgeable, most hardworking people in the world? Sure, they probably do have one or more of those qualities, but there may well be people with at least that much – and perhaps more – of the qualities that are required in order to succeed, and yet they don’t achieve the same levels of fame, success, money etc. Ever wondered why that might be?

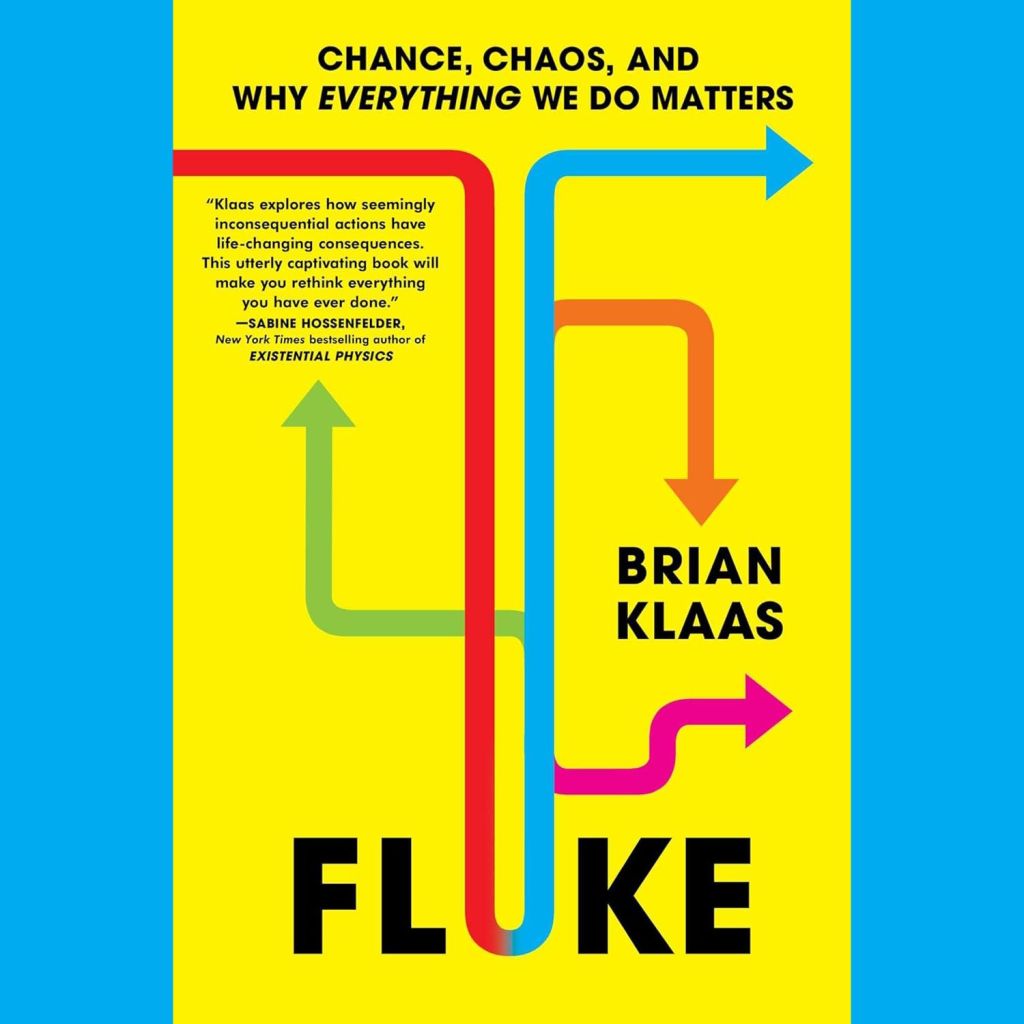

Author Brian Klaas’s (who is an associate professor in global politics at University College London) new book, Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters might have some answers. It is, according to the publisher’s note, ‘a provocative new vision of how our world really works, and why chance determines everything.’ The book is a deep-dive into the fascinating phenomenon of randomness and suggests that random events drive the ways in which the world really works. In the book, Klaas sets out to tackle some big questions, the answers to which affect pretty much every individual on the planet. Does everything happen for a reason or does stuff… just happen? Why do tiny changes sometimes produce huge impact? Is it possible to tame random happenings with the use of bigger datasets and sophisticated probability models? And can we live better, happier lives by embracing – rather than fighting – the chaos of our world?

‘We imagine the little stuff doesn’t matter much because everything just gets washed out in the end. But if every detail of the past created our present, then every moment of our present is creating the future, too. The central metaphor of the story is that humans are wandering through a garden in which the paths available to us are constantly shifting. In any given moment, we must decide where to take our next step. When we do, the possible paths before us change, forking endlessly, opening up new possible futures and closing others down,’ says Klaas. ‘But the most astonishing revelation is that our paths are not determined solely by us; it is not just our steps that matter because the paths through our garden are also constantly being moved by the decisions of living people that we will neither see nor meet. The paths we decide to take our redirected, our trajectories diverted, by the details of other lives, which we never notice,’ he adds. A bit like the game of Chinese Checkers, then. Those who are familiar with the game know that winning or losing depends not just on the moves one makes, but also the moves that other players are making, which may work out in favour of one player and go completely against another. It’s all random, everything depends on ‘chance.’ The world might well be a gigantic game of Chinese Checkers that’s being played between billions of players, most of whom will never even see or meet each other. A bit scary? A major deviation from the comfortable notion of ‘reality’ as we know it? Yes, and the book makes it clear that we need to learn to deal with this.

One example of complex uncertainty quoted in Fluke pertains to the extinction of dinosaurs, millions of years ago, when a nine-mile-wide asteroid hit planet Earth with a force that was 10 billion times that of the atomic bombs that wiped out the Japanese city of Hiroshimia in 1945. That asteroid came from oscillations in the Sun’s orbit – small gravitational disturbances caused that asteroid to hurtle through space and hit our planet, but if those disturbances had been microscopically different, the asteroid may have gone elsewhere, missing Earth entirely, thereby sparing the dinos and, perhaps, drastically altering the future of our planet. ‘If you squint at reality for more than a moment, you’ll realise that we’re inextricably linked to one another across space and time. Everything we do matters because our ripples can produce storms – or calm them – in the lives of others,’ says Klaas. ‘That means we control far less of our world than we think we do, because Earth-shattering events can develop based on strange, unexpected interactions that are nearly impossible to predict,’ he adds.

Does this mean that human effort – the conscious initiatives we take in order to get ahead in life – may not be very useful? That isn’t really what Fluke is trying to convey. Instead, what we need to understand is that luck – that contentious word we use to describe random happenings in life – might play a bigger role than what we’re willing to accept. So, for anyone who has felt bad about not having more money in the bank, a bigger car and a bigger house – here’s something that might give you some comfort. Klaas tells us that in a recent study, physicists teamed up with an economist and used computer modeling to develop a simulated society with a realistic distribution of talent among individuals. In this computer-simulated world, talent mattered, but so did luck. The simulation was run repeatedly to see which individuals would be most successful and in the results that came out, the person who became the richest was never the most talented but always someone close to average. What this might mean is that Mukesh Ambani and Gautam Adani aren’t necessarily brilliant. Sure, they’ve worked hard and worked relentlessly, but they also got lucky, because, hey, there are countless others who work just as hard (or harder) and are at least as intelligent (or more) than those two. ‘Some billionaires may be talented. All have been lucky. And luck is, by definition, the product of chance,’ says Klaas. And, of course, it’s not just billionaires – there’s an element of luck, of randomness, in all our lives. Right from the time we’re born, the smallest of things we do, together with the actions of those around us – near and far, known and unknown – determine the trajectory of our lives.

‘We are the offshoots of a sometimes wonderful, sometimes deeply flawed past, and that the triumphs and the tragedies of the lives that came before us are the reason we’re here. We owe our existence to kindness and cruelty, good and evil, love and hate. It can’t be otherwise because, if it were, we would not be us,’ concludes Klaas. As for the book itself, Fluke sits at the confluence of science, mathematics, history, sociology and philosophy, and combines elements from each of those to explain life and the ways in which things pan out. Or don’t. It’s an interesting, thought-provoking read and requires that you keep an open mind and be willing to at least consider the author’s take on life and luck and why everything matters. Long after you’ve finished reading it and kept it in your bookshelf, you might find yourself still thinking about Fluke for a long, long time.

Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters

Author: Brian Klaas

Publisher: Hachette India

Format: Paperback / Hardcover / Kindle

Number of pages: 336 / 336 / 316

Price: Rs 1,561 / Rs 1,779 / Rs 319

Available on Amazon

Book Review: Fluke – Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters