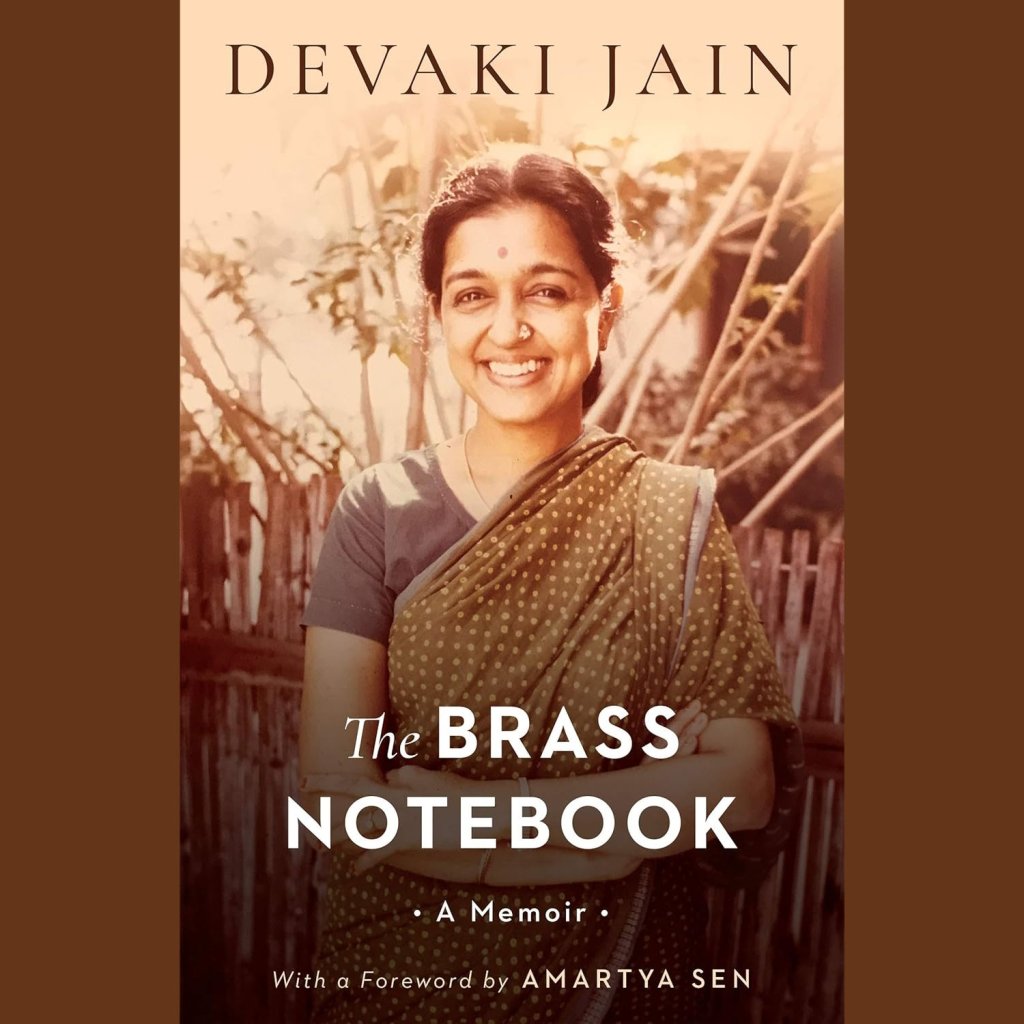

‘In this no-holds-barred memoir, renowned feminist economist and academician Devaki Jain recounts her own story and also that of an entire generation and a nation coming into its own,’ says the publisher’s note, about The Brass Notebook. Jain writes about her childhood in south India, a life of comfort and ease with a father who served as dewan in the Princely States of Mysore and Gwalior, of growing up in an orthodox Tamil Brahmin family, the restrictions imposed upon her and the lurking dangers of predatory male relatives. The author, who got her first taste of freedom when she went to Ruskin College, Oxford, in the UK (where she studied for a degree in philosophy and economics), also writes about her romantic liaisons in Oxford and Harvard, and falling in love with Lakshmi Jain, whom she married against her father’s wishes.

Later in life, Devaki’s became deeply involved with the cause of ‘poor’ women – workers in the informal economy – and she worked towards helping these women live better lives. ‘Her work brought her into contact with world leaders and thinkers like Vinoba Bhave, Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Henry Kissinger, Amartya Sen and others. In all these encounters and anecdotes [which she recounts in the book], what shines through is Devaki Jain’s honesty in telling it like it was,’ says the publisher’s note.

‘This is a wonderful memoir of someone who has an extraordinary recollection of interesting things happening around her and who writes about them beautifully. Apart from its originality, the memoir is enriched by the fact that throughout her life, Devaki has been close to people of great interest. Of course, among the people whom Devaki came to know well was her extraordinarily talented partner – later her husband – Lakshmi Jain. While each lived exceptional lives of their own, together they built an existence larger than the two combined. This is a most readable account of experiences – attractively recalled and elegantly presented,’ says Amartya Sen in the foreword he’s written for the book.

‘Writing this story of my life has been like coming off a ship, wrecked by a storm, or out of an ancient cave in the mountainside, as everything that I try to remember seems long ago and yet like yesterday. A journey spanning seven decades of ‘adult’ life is certainly a long one. It was natural that there were many waves, storms and stillnesses that I witnessed over those eras and I thought my experiences may reveal some new pictures from the big picture, painted by historians. Persons who may have lived, say, seventy adult years in other periods may find my stories trivial or commonplace but that is in fact the excitement of history. That in some ways it is never new, nor ever old,’ says Devaki.

With the publisher’s permission, here is an excerpt from Devaki Jain’s memoir, The Brass Notebook

Until my family moved north to Gwalior, I had little knowledge of the political turmoil in India. ‘British bootlicker,’ my classmate once shouted at me. We were both schoolgirls, the only two non-Christians in our class at the Sacred Heart Convent in Bangalore. The year was 1942. Our school was at the centre of an area of Bangalore called the Cantonment. It had been built to house British soldiers and other colonial officials. But other communities lived there too—Anglo-Indians, products of mixed marriages, usually between British men and Indian women, converts to Christianity, and Tamil-speaking migrants from the nearby state of Tamil Nadu, brought to the Kannada-speaking city of Bangalore in part so that the British ruling class needn’t depend on the local labour supply.

The school was large and had several buildings, mostly made of the famous grey sandstone of the Deccan plateau on which Bangalore stands. Over time, the grey stone had turned a dignified, muddy brown. The house I grew up in too, was built with this stone; it was the most popular building material at the time, easy to maintain because it didn’t demand regular painting, and calming in the way it blended with the local flora. The buildings of my school housed a chapel, a hostel for the nuns as well as one for the students, and classrooms. The grounds were extensive, with courts for basketball, tennis and other sports.

While most of the other students, largely Anglo-Indian or Goan Christians, would walk or cycle from their nearby homes, my younger sister and I came to school every day, to our great embarrassment, in a coach drawn by a beautiful chestnut brown horse. There were no buses or any form of public transport from where we lived, to the Cantonment. It was like two different cities. I loved the various prayers and litanies that were part of the Roman Catholic tradition of the school. I would go to the chapel, make the sign of the cross, sing all the hymns, ‘do’ the rosary (a friend gave me one to pray with). The rosary had to be hidden when I was at home, and my private devotions restricted to the bathroom. Like so many girls who feel the aesthetic appeal of Catholicism, I wanted more than anything to be a nun. Of course, I breathed nothing of these thoughts to my family at home, upper-caste Hindus who would have been shocked at one of their children abandoning both her family’s religion and hopes of a happy domestic life.

As it was, we were not allowed to enter the house proper without first shedding our uniforms, bathing and changing in the bathroom, which we were to enter by the back door. We had two very orthodox grandmothers living with us who regarded close proximity to Christians as polluting. Out on the streets, nationalist sentiment was growing. The anti-colonial struggle was at its peak. Mahatma Gandhi’s call, in 1942, was for the British to ‘Quit India’. But almost nothing of that movement resonated inside the house; we were not avid newspaper readers. My father was a civil servant who served the Princely State of Mysore: the State had, since the early nineteenth century, retained a certain measure of independence but at the cost of ceding much of its former power to the British.

The Princely States were somewhat cocooned from the nationalist tumult, though in Mysore State, this insulation from politics allowed for a policy of successful industrialisation by a succession of progressively minded rulers guided by extremely competent and far-seeing dewans. Moreover, civil servants in those years tended to stay aloof from the political struggles on the street. My friend at school came from a business family deeply involved in politics, for it was the commercial (rather than professional) class that was more supportive of the freedom movement. She had grown up in quite a different atmosphere. Politics for her had been the air she breathed. Of course, my family, relatively uninvolved with the freedom struggle, would seem to her like sycophants of the British. To my class fellow, my father’s position in the colonial bureaucracy was enough to expose me as a ‘toady’. The sense of hurt and humiliation was strong when she taunted me. I wasn’t sure what a bootlicker or a toady was, and why I was being accused of betraying my country.

This abuse had come my way because of the enthusiasm with which I had taken part in preparation for a visit by a British school inspector. An enormous map of the world had been brought out, and the students had been asked to colour in red the countries that were colonies of the British Empire and stick little Union Jacks onto them. To go with this was a song called ‘The Triumph of the British Empire’ hailing the British monarch. I had worked on this map-fixing the whole morning with other students and then learnt and sang the song with such energy that the nuns who taught us, chose me to lead the procession and deliver a speech of welcome to the British school inspector!

All this I had done in perfect innocence, and it was what provoked the abuse from my anti-colonial classmate. It was, effectively, my introduction to politics, to the outside world, and it unsettled me. In a way, the awakening lasted for the rest of my life.

The Brass Notebook: A Memoir

Author: Devaki Jain

Publisher: Speaking Tiger

Format: Paperback

Number of pages: 248

Price: Rs 414

Available on Amazon

The Brass Notebook: An Excerpt