Consigned to the shadows, their very existence swept under the carpet, the transgender community in India – even as it struggles to somehow eke out a living at the fringes of society – faces widespread ridicule and humiliation. The challenges they face have often been documented in the media but have never been adequately addressed. The society, for the most part, is not able to understand the transgender community and what we don’t understand, we often fear and oppose.

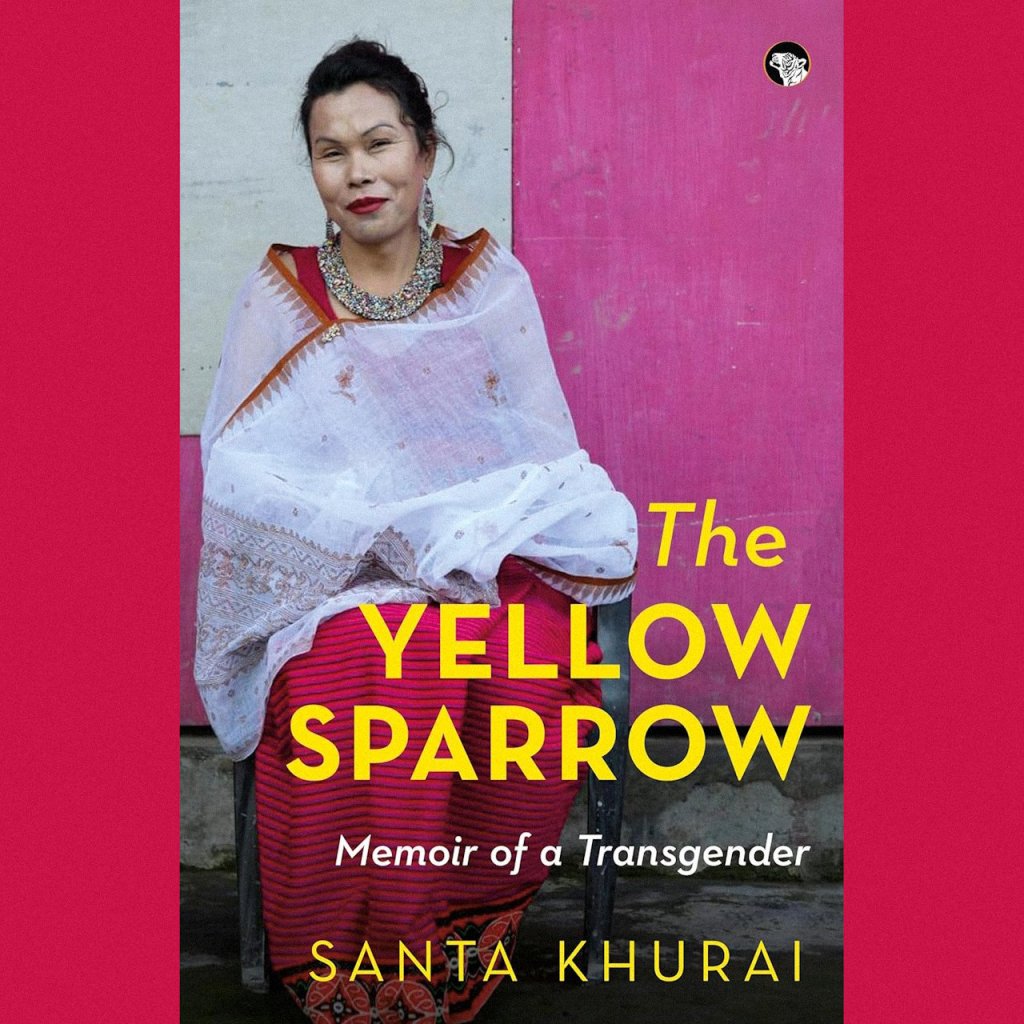

Born male, Santa Khurai always believed herself to be female and was 17 when she started dressing like a woman. The fact that she wore dresses and make-up in public made her father immensely angry; she had to face insults and ridicule wherever she went, and was often beaten up by the armed forces that are a constant presence in her native Manipur. She found it hard to find work and even though she was eventually able to open her own beauty parlour and found success as a make-up artist, the stress she had to face every day sent her spiralling into drug abuse and penury. In The Yellow Sparrow: Memoir of a Transgender, she documents her struggles and recounts the story of her life – an inspiring saga of how the indomitable human spirit can overcome seemingly impossible odds.

‘This memoir is based on various events, trials and tribulations I have faced in the past many years. I have chronicled the events of my life in the simplest manner. Looking back at the events recorded here, I realised that Manipuri society has changed in many ways, and along with these changes, the conditions of Nupi Maanbis, or transgender women, in this region has also changed. Remembering attitudes and social conditions of the past gives new impetus to the present, and most importantly, a new hope,’ she says. ‘Since I was considered a person who was ‘different’ from others, not many people were interested in listening to my problems and frustrations. This suppressed pain and anger led to a feeling of relief and bliss the moment I started reliving those moments and writing this memoir. The feeling of lightness was akin to what one experiences when sharing one’s burdens with friends,’ she adds.

With the publisher’s permission, here is an excerpt from The Yellow Sparrow

He spoke to me as though we had been best buddies for ages. ‘Pal, how are you? Look, there is a little something I have to tell you. Should we walk towards the gate?’ The stranger’s behaviour immediately created doubts in my mind. But I did not want Ema to think that there was anything amiss. I complied with the unknown youth who was posing as my friend for whatever reason. As we reached the middle of the shumang, the man put a gun, hidden from Ema’s sight, to my back and whispered threateningly, ‘Tell your mother that you will be back in a while, tell her you are not going too far away.’

I followed his instructions. ‘Ema, it is my friend from MBC. I will be back in a while.’ Ema replied, ‘Come back as soon as possible. Do not go beyond Ebok Ebetombi’s house.’ The stranger did not remove his gun. We continued walking towards the gate. Dusk was falling and the thick growth of cedars and acacia trees made our locality ominously dark. There was no public lighting system in our locality in those days, the entire neighbourhood was completely dark after dusk. As the stranger and I walked towards the far end of the lane, I saw three more men were waiting for us. One of them asked, ‘Is this the one?’ The man who had led me out of my house mockingly replied, ‘Yes, this is the one.’ Another man said, ‘You miserable homo. His legs must be crippled.’

They pushed me further towards the Laishram neighbourhood. At the far end of Laishram was a vast paddy field, which was quite deserted at that hour. Just before the stretch of the paddy field began, there was a thick grove of bamboo. One man plucked a bamboo branch with which he started lashing at my legs. He asked, ‘Tell us what are you? Man or woman?’ In that very instance, another man kicked me from behind. I fell to the ground. One of the others slapped my face, I was mercilessly assaulted from every direction. My misery and abjectness seemed to be complete. It was strange, but at that very moment a kind of rage rose up inside me, and it clamoured to be heard. ‘Who are you? Why are you beating me?’ I managed to say.

My questioning them betrayed a courage and defiance they were not expecting. One of them punched my mouth. ‘You dare question us! We are the ones made to punish and educate people like you.’ He took my ability to speak up for myself even as they were assaulting me, as an insult. One of them commanded, ‘Lie on your stomach.’ There was no way that I could not comply. I could only hope for somebody to show up on the street. More than hope, it was a silent scream of utter despair—not a single soul heard me or saw me in that humiliating state of desperation. They continued beating me with the bamboo branch until I was raw and bruised all over. One of them forced me to hold out my hands. Seeing my painted nails, all of them laughed and spat in my face. Then, calling me ‘shameless homo’, the first man pushed my hands to the ground and smashed my nails with a brick. The torture continued for a while, without interruption. ‘If we ever find you walking in the streets in women’s clothing, that will be the end of you,’ one of them said. With this threat, the ordeal came to an abrupt end.

Somehow, I managed to reach home in that injured state. Ema was clueless about what had happened, she asked, ‘Who were those people?’ Examining my swollen face, she anxiously asked, ‘What happened? Who did this to you?’ I replied, ‘Those people who just came did this to me.’ Ema pressed me, ‘Why did they do this to you?’ I said matter-of-factly, ‘Because they say that I wear women’s clothing.’ At this, Ema broke into a wail. ‘We have been trying to tell you your behaviour is not acceptable. Ours is a difficult time. Many pose as naharols, guns are also easily available. You should be careful. Be afraid.’

I said, ‘I am not scared. This is happening to me because you brought me into this world.’ Ema wiped my bruised and bleeding face. ‘You have to be very careful. We are living in very bad times.’ I replied coldly, ‘I don’t care. I will retaliate.’ ‘Well then. You are courting your death,’ Ema said with a sigh. ‘Do not let the neighbours know what happened to you. Try to understand.’ I sensed the hopelessness of a mother in her reply.

I replied, ‘I do not care about death now.’

Note: Santa Khurai will be in Delhi this weekend at the Rainbow Lit Fest. For those who wish to attend, you can book your tickets here

The Yellow Sparrow: Memoir of a Transgender

Author: Santa Khurai

Translator (from Manipuri to English): Rubani Yumkhaibam

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

Format: Paperback / Kindle

Number of pages: 328 / 290

Price: Rs 424 / Rs 393

Available on Amazon

The Yellow Sparrow: An Excerpt