To be released later this month, Lab Hopping, co-authored by Nandita Jayaraj and Aashima Dogra, is an introspective look at women scientists across India, highlighting the challenges they face and bringing their stories to the world. The authors travelled across the country, speaking to well-known women scientists as well as researchers who are at a relatively early stage in their careers, and documented their accomplishments and the issues they face on a daily basis. The book offers ‘fresh perspectives on the gender gap that continues to haunt Indian science today,’ the authors say. ‘Our labs are brimming with inspiring stories of women scientists persisting in science despite facing apathy, stereotypes, and sexism, to systemic and organisational challenges. Stories that reveal both a broken system and the attempts by extraordinary women working to fix it.’

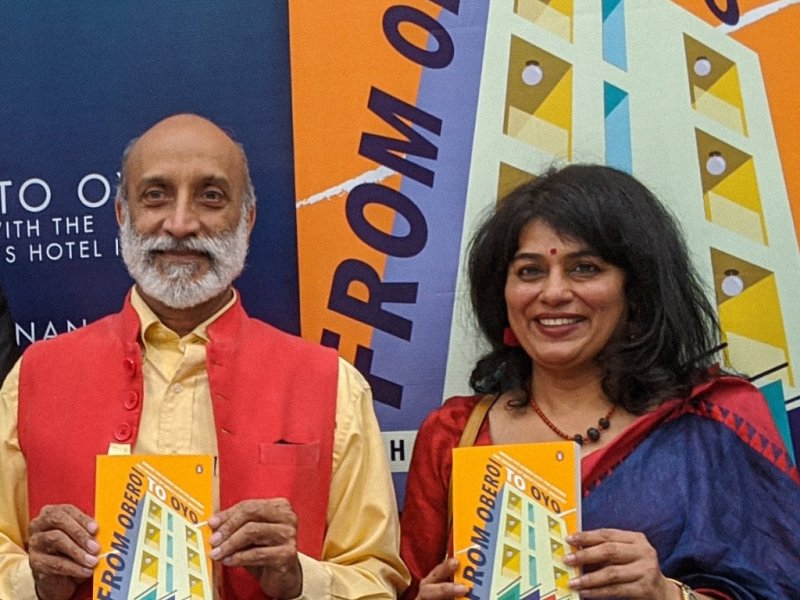

Bangalore-based Nandita has a Master’s degree in Bioinformatics and a PG diploma in new media journalism, while Aashima, who is currently based in Vienna, Austria, has an M.Tech in Biotechnology and an M.Sc in scientific research and communication. They are co-founders of TheLifeofScience.com (TLoS), which they set up back in 2016 and which they continue to run. BooksFirst caught up with them to talk about Lab Hopping, the barriers that women scientists face in India, the challenges they deal with, and the changes they would like to see in the world of science.

Please tell us about your deep interest in science. What was it about studying biotechnology / bioinformatics that you found most fascinating? You have both studied journalism as well. Did you always want to be writers / journalists, writing about science and technology?

Nandita: I went to school at the time when the craze for engineering was peaking and every academically-above-average student was pushed to study science after 10th standard. I liked science and maths, but looking back I think that was a narrative pushed on me merely because I scored well in those subjects. In reality, I was probably equally or more interested in reading, writing and art. Studying biotechnology was kind of a random decision I made largely due to the advice of family members, influenced by what other people in our social circles were doing at the time. I completed my bachelor’s uneventfully and uninspired, without any real love for what I’d studied. It was in my Masters’ in bioinformatics that I found myself in an environment where I put my mind into science and developed a fondness for it – I realised that I loved making sense out of complex concepts and sharing what I learnt through notes and seminars. I also realised – somewhat disconcertedly – that I enjoyed that aspect more than doing the actual experiments. That must be why I was so excited when I discovered that there was something called science communication and science journalism. During a short stint working at a radio station, I was also exposed to how liberating and meaningful it could be to work in media, as compared to the dry, serious and isolated labs I’d worked in so far. This affirmed my decision that science journalism was the path for me.

Aashima: I think I have always been deeply interested in science. The kid who comes home with the Tell Me Why books – that was me! I wanted to work on science stories, but I did not know it so clearly when I was pursuing my Bachelor’s degree. In those days, biotech was new and trendy. News of dolly the sheep – the first mammal clone, and other such stories blew my mind. The biopharma industry was growing and biotech research was abuzz. People told my parents: ‘There is scope in biotech.’ So it was an exciting choice. My first Masters was in Biotech; I was interested in research and all the applications that were possible with the new tools. But lab life was not for me, I realised quite late that my calling was in science stories and the promise of science to bring changes in the world. Hence, taking up Science Communication was an obvious choice. There were aspects of journalism in that training. Science is appealing to curious minds but that doesn’t make science communication simple. The trade is a bridge to many theoretical constructs that scientists are engaged in and the realities of people and communities. And that still keeps me motivated.

Tell us about The Life of Science. What was it that inspired you to set up TLoS? In setting up and running TLoS, what have been some of the biggest challenges that you faced? Also, in the seven years that you’ve been running TLoS, what have been some important highlights?

Nandita: Aashima and I met while we co-edited a children’s science magazine together in Bangalore. A number of experiences we had there (we recount these in the book) led us to the realisation that science was seen as a domain full of male geniuses, and is as heavily male-dominated as the broader society that it likes to set itself apart from. It bothered us because we felt that by perpetuating this image of science in our magazine, we were wronging our very young and impressionable science-loving readership. The magazine shut shop and the two of us decided to continue our science communication partnership with a blog that would document the lives and contributions of today’s women in science.

The idea may have come from the two of us, but right from the beginning we benefited from collaborations – with artists for comics, with technologists for our interactive lab-hopping map, and later with fellow science writers, podcasters, etc. TLoS expanded in a way that was very unexpected but amazing. Every year we started a new publication cycle and to help us, we would invite a third person to join our editorial team as coordinator. Often these were talented young people hoping to make science communication their career. Working with a new person for 6-8 months or more every year kept TLoS evolving. We are still close to most of our coordinators and it’s been very gratifying to see them find their niche, join their dream institute, win grants, teach at schools, work at international organisations, write picture books etc.

At TLoS, one thing that’s important to us is to not fall into the trap of judging who is worthy of having their story told, based on predominant markers of success like prestige of institute and awards won. We have always gone out of our way to tell yet untold stories and contributions that are otherwise likely to stay hidden because of our own biases – our inherent casteism, classism and flawed interpretations of ‘merit.’ This means we go to States and regions whose scientific contributions are usually overlooked, to universities which are usually severely underfunded, to people who have not had the kind of background and academic pedigree that is usually celebrated. Big names definitely gather more eyeballs, but once in a while a ‘hidden figure’ story becomes noticed and this has a very meaningful impact – not just for the scientist herself, but for the community around her.

The biggest challenge we’ve had in running TLoS is funding. We want to keep TLoS independent and informal, a collective without much of a hierarchy and full transparency. We realised that this is hard to do if we have any expectations of getting fairly paid ourselves and being able to fairly pay our collaborators. We have also found it really challenging to quantify the impact that we make with the project. This has come in the way of the success of our fundraising. The bright side of our reliance on crowdfunding has been the community-building that comes with it. Most of our supporters are regular people who see value in the work we do and give small amounts that they can afford. While the money we can raise in this way is limited, the quality of support we have received is immeasurable.

Coming to your book, is Lab Hopping a natural extension of TLoS? The book mentions that there is significant participation of women studying and teaching science in schools and undergraduate colleges but not enough women pursue scientific research as a career. What are some of the most important reasons that you would attribute to this, and what are the things that must change in order to resolve this situation?

Aashima: Yes, the book Lab Hopping is a natural extension of the lab hopping we have been doing in the last seven years, all of which is reported on thelifeofscience.com aka TLoS in different media formats. The answer to your next two questions, really, is the entire book. The gender gap in science in our country starts to appear after post graduate studies. This is different from the attrition patterns seen in other countries. In the US for example, there are less women taking up STEM. The blue and pink segregation is more stark there. In India however, women choose to leave the sciences since it is harder to secure a job, even more so, a permanent one. The culture in our labs rewards the scientists that can afford to stay in the lab for long hours and embody the identity of a genius scientist solely. Most Indian working women in contrast perform multiple roles in their families, communities and their place of work. But the most important reason behind the gender gap in India we found is the fact that women are not given the opportunities to first become a scientist and then to get ahead in the ranks.

Unlike many other fields, in science and academia one cannot just get a gig, one can only build. Without that award, training or research grant, it is hard to get the coveted position and recognition and so on. Sadly, the entire system is built upon hierarchies. It is just not an inclusive place. Diversity is important in science, and bias skews the results. Understanding what the issues are is not hard since there is much scholarship in the country about the sociology of science. We must also acknowledge the sexist, casteist and heteronormative roots of education in India and of science globally. That’s the first step. And there is a long way to go from there but ultimately, our science culture must change to be more inclusive. And since most science in India is publicly funded, the government-run institutions, especially the top ones, must take the lead.

Tell us more about the book. Regarding the research you did, on what basis did you select the women whom you met and spoke to for the book? Of all the places you travelled to, the institutes you visited and the women scientists you met, what were some of the most memorable highlights, which you would like to share with us?

Aashima: From the outset, we wanted a truly diverse pool of interviewees. That took us to institutes big and small, public and private, central universities and state universities, IITs and TIFRs, from PhDs to head of institutes. We were quite aware, from the beginning, that if we just went to the women scientists that were already recognised in some way, we would not get the right answers. So we focussed on the hidden figures. These resulted in original stories and our audience got to know women scientists working in their backyards that they had never heard of before. Most of these women’s stories were inspiring since they are defying the odds.

In 2019, we wrote a children’s book featuring 31 of these inspiring women, titled 31 Fantastic Adventures in Science. One of the chapters in that book features the first woman scientist we met, Natasha Gurung, who had been working to rid the Darjeeling Mandarin orchards of a viral infection in Kalimpong. She gave us a tour of her labs at the ‘Virus Office’ and told us about her scientific ideas to improve agriculture in the hilly region. In her story, we really saw an earnest dedication to employ science in order to solve problems and help her community. Another teaser I can share is what an interviewee said. I cannot name her but she is one of the top scientists in the country, doing very important work for India. She protested that even for women who reach the top, there is an expectation to stay silent and not ‘harp on’ about recognitions and awards. As if being allowed to do science for a woman should be enough! There is ongoing policing that dictates ‘you can do science, but you are not allowed to excel in it.’ But thankfully, that doesn’t stop her.

Regarding the women scientists you chose to speak to, for the book, were all the women very forthcoming and did they speak to you freely about the challenges they face at work, or did you also encounter some reticence? Did you find that some women weren’t willing to talk, perhaps due to fears of criticism or retribution?

Nandita: Experiences like sexism, casteism and harassment can be extremely risky for women to openly talk about – in fact several times I have felt that our labs are more protective of the harassers than the harassed. Since the bosses of science are largely still in denial of bias, anyone who points out unpleasant realities is branded a troublemaker and their career may very well be jeopardised. We were not surprised that some of our sources chose to stay anonymous while sharing particularly bitter experiences. One of the chapters in our book is titled ‘Hush Hush’ and it delves into the culture of silence that is severely slowing down Indian science’s goal of equity and quality.

That being said, by the time we started writing the book, we had already identified many scientists who had incredibly powerful stories to tell and were willing to tell it. So we never really had a shortage of forthcoming people to speak to. I think we had a tougher time with officials who were often reluctant to open up and got defensive when we asked them straightforward questions about problematic policies.

Among the places you went to and people you spoke to for the book, what were some common concerns voiced by most? What were some common issues that women scientists across the country are struggling with, regardless of geographic location? What patterns did you see in this context? Also, did you observe any specific, unique issues that were only endemic to certain regions?

Nandita: These questions are pretty much what we try to answer in 250+ pages of the book But let me try to sum it up. The issues are many, and some of them are well known and well acknowledged, whether or not they are being tackled in the right way – these include obstacles to girls’ education in society, culture of getting them married early, lack of childcare provisions, unofficial bans on hiring scientist couples, age limits during hiring. Even implicit and explicit sexism and sexual harassment is more understood and talked about these days than it was earlier. However, the problem is that all dialogues and interventions are very surface-level. Almost never will you see the government and institutions engage with the need to penalise those doing the discrimination in these above scenarios. We want to ‘acknowledge’ all the problems but we are not interested in implementing wilful measures to eliminate them. This can be seen in the vague nature of many of our policies such as the GATI charter and the draft STIP 2020.

People are also suffering because many of these issues – such as age limits, childcare etc – are being projected as cis-women’s issues when they are really not. Men have children too. Trans people are parents too. Moreover, while there is sympathy and empathy for marriage and motherhood-related issues faced by women in science, there is no sensitivity to other intersecting realities such as caste or disability which further marginalise women.

It’s difficult to talk about region-specific issues because scientists often work in places far away from where they grew up so it’s hard to do that kind of categorisation. We sometimes saw completely different challenges and points of view being faced by different individuals in the same institute! The diversity of upbringing and privilege is just too much and it’s impossible to generalise.

Let’s also talk about the brighter side of things. Of the cities you went to, institutions you visited and women you spoke to, were there any conversations about how women – at least some women – may have been wholly encouraged in their workplace, and how their work and their ideas may have been appreciated and promoted, especially by their male colleagues?

Aashima: Yes, there were. We heard often of such supportive colleagues – sometimes there were also men. But often this support is silent and limited. When it comes to the big time, like pushing for women to win top honours and standing behind victims of sexual harassment, this support seems to fall short. There are definitely truly feminist men in the community but also we witnessed obvious performative wokeness that only serves to appease all sides. This is also true for the many women supporters. What we need is top prominent scientists to start taking a stand consistently for not just one group but inclusivity across the board. We do have enough voices to spark an inclusive culture. Since the issues are systemic we need the trend setters to be more radical than they are – I mean, not shy away from taboo topics like ‘caste’ ‘sexual harassment,’ ask for accountability and be more vocal inside institutes and in top-level meetings.

To conclude, for women in India who want to make a career in science and technology, do you think there is light at the end of the tunnel? Do you think things will get better and prospects will get brighter?

Nandita: Absolutely! The light is in the form of many, many individuals within the flawed system who are fighting the good fight, not just for their own goods but for the benefit of future generations. What we realised after all these years is that the science establishment tries to project itself as superior, noble and objectively meritorious beyond any other, but the truth is they are no better for the marginalised than any other professional sphere. Women in India are remarkably smart about how to go on with their work in the face of sexism and we see dozens of examples of this in the book. A book like Lab Hopping is definitely not going to ward them off science. What the book can do is be a wake-up call to the authorities to stop dilly-dallying and tackle discrimination head on.

Lab Hopping: A Journey to Find India’s Women in Science, is available on Amazon

More Stories:

adventure advertising Allahabad Apple astrology audiobooks Banaras best-of lists Bombay book marketing business Calcutta cheap reads cityscapes corporate culture design fiction food Hinduism hippies history India Japan journalism journalists libraries literary agents memoirs memories money Mumbai music my life with books Persian photojournalism Prayagraj publishers publishing science-fiction self-help technology travel trends Varanasi wishlists